Political Economy of the Korean Screen Quota

Introduction

The Political Economy of the Korean Screen Quota System: The Actors, Their Interests, and Their Effects on the Korean Share of the Domestic Movie Market, 1983-2003

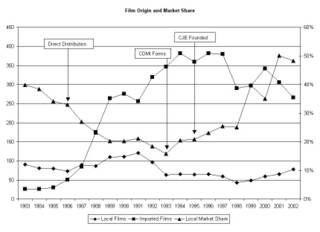

The fluctuations in the Korean share of the domestic movie market over the last 20 years are directly related to the interplay of the concerned parties. In the late 80s the Korean movie industry was politically weak relative to the U.S. Commerce department and the Motion Picture Association. This allowed American interests to push open the Korean movie market and capture huge market shares. However, in the mid-90s the Korean movie industry gained strength with the entrance of Korean conglomerates and the creation of the Screen Watchers Group. Since then, the Korean local market share has steadily risen.

History of the Screen Quota System

List of Actors

Pro and Anti Screen Quota Faction Members

The major anti-screen quota parties are the U.S. Commerce Department, the Motion Picture Association (MPA), the Korea Fair Trade Commission (KFTC), the Korean National Theater Owners Association (NTOA) and the Korea Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade (MOFAT). The pro-screen quota parties include the Coalition for Cultural Diversity in Moving Images (CDMI), Ministry of Culture and Tourism (MOCT), and Korean conglomerate branches engaged in the movie industry. Korean Presidential Administrations and the National Assembly have been fluid actors, alternately siding with the anti and pro screen quota factions.

The U.S. Commerce Department has made movie industry trade liberalization a central concern in its negotiations with Korea at least since the 80s. The U.S. Commerce Department repeatedly cited Article 301 of the Commerce Treaty between the United States and Korea as justification for opening Korea’s movie market to American companies. They were a central reason the Korean government passed the six-revised film law, which abolished the 2:1 Korean to American film ratio system and the USD $5 million annual import quota, in July 1987. In 2003, the U.S. Commerce Department made screen quota reduction below 20% a prerequisite to concluding a Bilateral Investment Treaty between the United States and Korea. Wendy Cutler, the assistant U.S. trade representative for North Asian affairs stated, “We would not conclude a bilateral investment treaty without adequately addressing the screen quota issue…. We’d never ask for the elimination of the screen quota. We are looking for Seoul to reduce the quota to an acceptable level.”

The MPA is the international branch of the Motion Picture Association of America. It was formed in 1945 as the Motion Picture Export Association of America and renamed in 1994. Since its inception, it has “cultivated ongoing support and political power from the US government.” The first president of the MPA, Eric Johnston, and his successor Jack Valenti “relentlessly lobbied the U.S. government (Department of State, Senate, House of Representatives and the President) to try and subside and/or annihilate the film trade barriers in Korea.” The MPA has primarily argued that trade liberalization would benefit all parties. In a March 26, 1999 meeting with then president Kim Dae Jung, Valenti predicted lowering the quota to “a reasonable and commercially acceptable limit” would encourage foreign financiers to invest “several hundred of millions of dollars” into “new state-of-the-art multiplex theaters in Korea.” He claimed, “A central marketplace truth is that neither parliaments, nor presidents can command their citizens to watch movies they do not choose to see.” Valenti cited the Korean film “Swiri” and claimed, “films that entertain and attract customers don’t need artificial crutches to win audiences.” More recently Jeffrey Hardee, regional vice president for the MPA said, “We are not trying to kill off the local industry. We just don’t think that quotas are an effective tool… [The quota does] local producers more harm than good… You have to hold local films longer than economically justified… Cinemas are essentially losing money. You’re not giving them flexibility.”

The KFTC’s predecessor, the Fair Trade Division, was established in 1976 “under the Price Policy Bureau of the now-defunct Economic Planning Board (EPB).” In 1981, the KFTC was formally established under the Office of Minister. In 1994, the organization “won independence from the EPB with the revision of the Government Organization Act” and in 1996 the Ministry’s “Chairman was elevated to ministerial level from vice-ministerial level”. The Ministry’s basic organization has changed little since then. The KFTC’s self described mission is “developing competition policy and enforcing competition laws. Its goals are to “promote competition in the market and to enhance consumer welfare.”

“The KFTC enforces the ‘Monopoly Regulation And Fair Trade Act’, under which cartels, M&As and abuse of dominance in the Korean markets are major targets of law enforcement. It also handles consumer protection policy and relevant laws. Active competition advocacy and regulatory reforms in the public sector are also major concerns for the KFTC.”

The KFTC has argued that the screen quota serves the interests of the Korean film industry at the detriment of the overall economy. Kang Chul-kyu, head of the Fair Trade Commission argues, “Domestic film’s market share has gone up more than 50 percent… The screen quota needs to be relaxed to encourage competition in [the] film industry….”

The predecessor to MOFAT, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, was established in1948. From the beginning it took charge of “diplomacy, external economic policy, overseas Korean nationals, international situation analysis and overseas promotional affairs.” The ministry underwent its only significant reformation in 1998. The “Ministry of Foreign Affairs was reorganized as the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade with the incorporation of the newly established Office of the Minister for Trade, so as to comprehensively establish and conduct foreign policies on trade, trade negotiations and foreign economic affairs.” This change did little to alter the Ministry’s responsibilities. It simply clarified longstanding practice.

The MOFAT has said the advantages of reducing the screen quota far outweigh the disadvantages. Kwon Tae-shin, deputy minister for international affairs at MOFAT stated: “South Korea’s exports to United States amount to $33 billion a year, but American films account for $200 million in the local film market. Being swayed by some self-centered people in the film industry is not desirable at all. A failure to sign a bilateral investment treaty will damage our export industries… Local films represent more than 45 percent of the movie market, and the film promotion fund has raised over 100 billion won [USD $82.4 million]. Thus, Korea’s film market is ready to be opened.”

The NTOA is composed of independent theater owners. In the early 80s, before foreign direct distribution was allowed, theater owners were among the most powerful interests in the Korean film industry. Theater owners controlled the movie distribution process through regional cartels. Movies always opened in Seoul “and then the studio [sold] the rights to the movie theaters in the various regional divisions.” Because there were “no simultaneous nationwide film releases… it [was] difficult to get an accurate count of box office receipts outside of Seoul.” Therefore, local “studios simply [sold] the rights to the film at a fixed price to theaters in each regional division, regardless of the commercial success of the film.” This gave the regional theater cartels tremendous power to set prices and make profit. If a film was “rejected by the people in charge of the regional cartels, it usually [ended] up in storage and [was] never released.”

Independent theater owners begin to loose their hold on the local film industry when foreign direct distribution was allowed in 1987. “Hollywood-related direct distribution companies, such as United International Pictures … were known to engage in illegal practices such as ‘block booking’ (selling several films to cinemas as a package deal, typically including a hit film and several less popular movies.)” Theater owners were forced to go along with the practice and pay large sums of money for movie rights because of the popularity of Hollywood films. “The Hollywood block busters that were supplied by these distributors would be the top box-office draws of local cinemas.” This practice severely weakened the power of independent theater owners.

But, the filial blow came 1993 with the formation of the Screen Watcher’s Group, the forerunner of the CDMI. Until then, the independent movie owners were virtually ignoring the screen time regulations outlined in the screen quota in order to show high-grossing Hollywood films. The Screen Watcher’s Group began to force the Korean authorities and independent owners to follow the law. This created serious market distortions, such as in the summer of 2001, when there were only 7 Korean movies for 216 screens in Seoul. In 1995, after the number of screens in Korean shrunk for the 5th year, the NTOA filed a complaint with the Constitutional Court asking it to repeal the screen quota system on the grounds that it “infringed on their constitutional guarantee to pursue economic happiness.” The organization argued the screen quota system was unconstitutional because it inhibited the theater owners’ free choice and their right to pursue their economic interest. They believed the screen quota placed an undue burden on theater owners by forcing them to subsidize Korean movies. They blamed the system for the dramatic drop in the number of independently owned theaters over the previous decade. However, the Court ruled the “The constitution guarantees the right to pursue happiness, however, this does not guarantee unlimited pursuit of economic interest irrespective of the interest of the community.” The Court’s decision denied the NTOA’s last chance for regaining power. The number of independently owned movie theaters in Korea has continued to decline unabatedly since then.

The most public member of the pro-screen quota group is the MCT. It is a relatively new bureau, which assumed its present form and responsibilities in 1998. Previously some of “its duties were handled by the Public Information Office and the culture division of the Ministry of Education, which were … established in 1948.” Then in “1961, the Ministry of Transportation set up a tourism department that carried out similar duties to the tourism division of the ministry.” At the same time the “Ministry of Information was established, and it took the parts of art and cultural affairs from the Ministry of Education.” Then in “1968, the Ministry of Information was replaced by the Ministry of Culture and Information.” It took charge of Korea’s “cultural property and management of the museums from the Ministry of Education.” The Ministry of Culture was set up in 1990 and “printing, broadcasting and other mass media-related affairs were transferred to the Ministry of Information.” In 1993, “the Ministry of Sports and Youth, and the Ministry of Culture were integrated into the Ministry of Culture and Sports.” And in 1998, “the Ministry of Culture and Sports was replaced by the Ministry of Culture and Tourism.” The new bureau “began handling affairs relating to the print and broadcast media, which had been the responsibility of the former Ministry of Information.” Until the responsibility for mass media was returned to the newly created MCT, previous ministries were primarily concerned with film censorship. However, after a landmark Constitutional Court ruling on October 4, 1996 that concluded film censorship violates constitutional law and National Assembly revisions to the Film Promotion Codes on March 17, 1997, the MCT took up screen quota protection.

With the appointment of the Chang-dong Lee as the new minister of the MCT in early 2003, screen quota protection became the Ministry’s central concern. Lee was the former president of the executive committee of CDMI, an interest group that represents the Korean film industry. He was “inaugurated as Minister of Culture and Tourism with the help of the strong support from the Korean cultural milieu as well as the Korean film society.” He stated, “I have no plans to make any change to the screen-quota system” and argued “The screen quota is not just an issue for the film industry; it is vital to the future of our visual media industry as a whole. If we lower our guard on film, the rest of the market is lost.” He doubts that the Bilateral Investment Treaty will bring significant benefits to the Korean economy. “We will not get [USD] $4 billion in new investment be concluding a bilateral treaty… an although there would be some benefits, the nation’s cultural sovereign cannot be given up for any gain.” He claims the culture sector is closely related to Korea’s national identity and points out, “Even the World Trade Organization’s Doha Agenda on the service sector excludes culture from its negotiations.”

The CDMI was created in 1993 as a “watchdog for the Korean movie industry” to “effectively enforce the screen quota system.” The president of the group, Gi-na Yu, prior to the formation of the CDMI the screen quota system “existed in name only with many theaters ignoring it and opting to pay the inconsequential fines instead.” She claims: “Things began to change after the establishment in 1993 of the coalition, then called Screen Quota Watchers, and through their lobbying efforts, the screen quota policy began to be enforced. The guarantee of a certain number of screenings made domestic companies willing to invest more at the production level and raised the overall quality of Korean films”

Samsung’s partial investment in “Marriage Story” in 1992 began widespread corporate involvement in film production. Both Samsung and Daewoo opened production studios and distribution companies in the mid-90s. Their large distribution networks enabled them to successfully compete with the foreign direct distribution companies. Daewoo pulled out of the movie business in 1998. However, Samsung’s subsidiary, CJ Entertainment and Cinema Service, which Samsung later bought, “challenged the oligopoly of the five [American] direct distribution firms.” By the time “Swiri” was released, “the stranglehold of [American] direct distribution firms… was broken.” By 2003, CJ Entertainment and Cinema Service captured 40.8% of the local market and distributed six of the top ten most-attended movies in Seoul.

The political establishment apparently took little notice of the screen quota issue prior to the late-90s. There are no reports of politicians making public comments regarding the system in English-language papers until 1998, when then presidential hopeful Kim Dae Jung included maintenance of the screen quota in his campaign platform. As president, Kim promised to maintain the screen quota system until the share of domestic movies reached 40%. However, he did not abolish the system when the time came. A majority of the national assembly signed a petition to maintain the screen quota in 1998 and the body passed a resolution to maintain the mandatory screening period for domestic films in 1999. Roh Moo-hyun campaigned on a pledge that he would maintain the current quota system. In general, the political establishment is in favor of the current screen quota system. “Their interest is to keep the quota in order to maintain the close relations with actors and actresses, who play a critical role in drawing public votes during the election campaigns.”

History of Actors

The Actors’ Effects on the Local Market Share

Comparisons between the actions of the parties concerned with the screen quota dispute and fluctuations in the domestic share of the local market show the actors had a direct effect on market share. The shift in aggregate power from the anti to the pro-screen quota faction caused the local market share to drop and rise over the last 20 years. The two most important changes regarding the screen quota in the last 20 years come in 1986 and 1993.

At the beginning of the 80s, the anti-screen quota faction was far stronger than its rival. The United States Commerce Department had been active in Korea since its formation in 1948 and had a long history of successfully negotiated trade agreements with the Republic of Korea. Its most important tool was Article 301 of the Commerce Treaty, which restricted market protection.

The MPA, likewise, had a long history in Korea dating back to the 1950s. It had been lobbying the American Government to open closed markets such as Korea’s for decades. The MOFAT’s predecessor, the MOF, had a longstanding relationship with the U.S. Commerce department. Its stated mission was to coordinate “external economic policy.” The FTC was formed in 1981 as a department under the control of the Economic Planning Board. Its purpose was to “promote fair competition and trade.”

The NTOA, which later became staunchly anti-screen quota, was less opposed to the system in the early 80s. It was the most powerful domestic group in the Korean movie industry and had benefited under the screen quota. The regulations were not being fully enforced during this period, so it had some leeway to pursue its own interest. However, the screen quota system blocked movie owners from obtaining highly profitable Hollywood movies. But most importantly, because the national movie theater owners’ cartels were organized in regional, rather than a national, cartels they were not organized enough politically to be a powerful force.

The pro-screen quota faction, on the other hand, was far weaker. Its two most important members, the CDMI and the entertainment branches of the conglomerates, did not exist. The only permanent member of the faction, the MOCT, existed as Ministry of Information and its main concern regarding movies was censorship rather than cultural protection. The non-aliened actors, the politicians, presumably held weak views on movie industry barriers and cultural protections. There are no reports of politicians making public comments regarding the system in English-language sources prior to 1998. Judging by their decisions to reduce the screen quota 146 days in 1985 and to allow foreign direct distribution in 1987, they valued free trade or bilateral relations over the interest of the Korean movie industry.

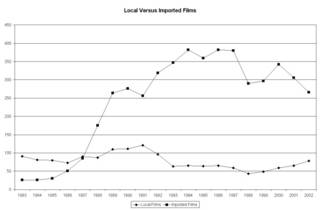

In 1997, the Korean government passed the sixth revised film law. This marked a watershed in the domestic movie industry. Previously, Korean law allowed only Korean distributors to supply foreign movies to the domestic market; stipulated theater owners show 2 Korean movies for every foreign movie; and set a 5 million dollar ceiling on annual foreign movie imports. The sixth revised film law abolished the ratio system and import ceiling. But, most importantly it allowed American distributions companies to negotiate directly with Korean theater owners. The number of imported films rose drastically. In 1985 there were 30 imported films. In 1989, four years later, there were 264 imported films in Korea. The number peaked at 384 imported films in 1994.

The Korean share of the domestic market, which was already shrinking due to poor Korean movie quality, lack of capital, and inadequate distribution systems , declined drastically. It went from 33% in 1986 to 20.2% in 1980 and bottomed out at 15.9% in 1993.

The entrance of the foreign distributors broke the strength of the independent theater owners’ cartels. The owners were highly dependent on Hollywood distributors because of the popularity and profitability of American movies. They were forced into disadvantageous deals such as “block booking,” or buying a package of movies that included several less popular movies and one hit movie. The independent movie theater owners were at such a disadvantage by the late 90s that they were going out of business. In 1991, there were 762 screens in Korea. By 1995, there were only 577. This is a drop of 185 screens.

The drop in Korean market share of the domestic market began to reverse in 1993. The formation of the Screen Watchers Group marked the shift of power from the anti-screen quota to the pro-screen quota system faction. The relative positions of the majority of the anti-faction, U.S. Commerce Department, the MPA, the KFTC, and MOFAT, remained largely the same. The KFTC gained independence from the Economic Planning Board, but nothing else changed. However, the Screen Watchers Group immediately affected the local market share. Prior to that time, the screen quota laws were not being enforced. Theater owners regularly ignored Korean movies in favor of higher grossing American movies.

But, with the screen quota being enforced, the Korean share rose nearly 5% from 15.9% to 20.5%. This reversed a decade-long decline in local market share in the domestic movie market. The next major boost came in 1995 with the establishment of Cinema Service and then CJ Entertainment. Encouraged by the gains made since the screen quota begin being enforcement and the protections the system provided, the conglomerates sunk money, technology, and talent into the Korean movie industry. CJ Entertainment started building its own distribution network with the creation of the CGV multiplex theater chain. This guaranteed outlets for its productions and reduced distribution costs. CJ Entertainment and Cinema Service’s aggressive market strategies broke the foreign distribution monopolies that controlled the local market since it was opened in 1986.

In tandem with these developments, the Constitutional Court ruled that film censorship violates constitutional law. This forced the MOCT’s predecessor, the MOC, to shift from censorship to cultural protection. Buy the time the current MOCT was formed in 1998, the organization was fully devoted to its new mission. This included protection and promotion of the screen quota. The MOCT has been a leading public defender of the system over the last 5 years, especially with the appointment of its new minister, Chang-dong Lee, a Korean movie industry insider, in 2002.

Politicians have joined the pro-screen quota faction in recent years as well. As mentioned above, they have realized that actors and actresses draw votes during election campaigns. Therefore they have supported the screen quota. Presidents, Kim Dae-jung and Roh Moo-hyun campaigned on a pledge that they would maintain the current quota system. A majority of the national assembly signed a petition to maintain the screen quota in 1998 and the body passed resolution to maintain the mandatory screening period for domestic films in 1999.

This shift of power from the anti to pro-screen quota faction has caused the local share of the Korean market to rise from 20.9% in 1995 to 39.7% in 1999. In 2001, the Korean share of the domestic movie peaked at 50.1%; its highest in over two decades.

Local Versus Imported Films

Local Market Share

Overview: Film Origin and Market Share

Summary

The above description illustrates that the fluctuations of the Korean market share in the domestic market are dependent on the interests of the predominate groups. From 1983 to 1993, the anti-screen quota faction was stronger and the Korean market share fell to 15.9%. However, as the pro-screen quota faction gained power in the period 1993 to 2002, the Korean market share rose to a peak of 50.1%.

Works Cited:

Kim Young-hoon, “Outlook: Screen Quotas Make Little Sense,” JoongAng Daily (Seoul), 23 June 2003.

Coalition for Cultural Diversity in Moving Images, “Overview of the Screen Quota System in Korea”; [on-line] available from http://www.screenquota.org/epage/Board/view.asp?BoardID=4&Idx=81; Internet; accessed 5 May 2004

Byung-il Choi, “When Culture Meets Trade: Screen Quota in Korea,” Global Economic Review Vol 31, No. 4 (Seoul, Korea: Korea Institute for International Economic Policy, 2003), 78.

Kim Byong-Jae, “Currents: The Unmaking of the Korean Movie,” Koreana Vol.6 No.4 (Seoul: Korean Foundation, 1992)

“U.S. Aide Says Korea Not Ready for Free Trade,” JoongAng Daily (Seoul), 22 October 2003

Wikipedia: Free Encyclopedia, s.v. “Motion Picture Association” [on-line] available from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Motion_Picture_Association; Internet; accessed 13 June 2004

Brian Yecies, “Re: Regarding your Screen Quota Research,” (summary of current research regarding Korean Screen Quota System in e-mail response to inquiry, 5 May 2004).

“Valenti Discussed Renaissance of Korean Film Industry with Korean President,” (Los Angeles: Motion Picture Association of America, 1999) [online] available at http://www.mpaa.org/jack/; Internet; accessed 5 May 2004

Don Kirk, “South Korea’s Filmmakers Roll Into Action to Protect Foreign-Movie Quota,” International Herald Tribune (Paris), 11 December 1998

Korea Fair Trade Commission, “About the KFTC: History,” (Seoul: KFTC, 2004) [online] available at http://ftc.go.kr/eng/; accessed 10 June 2004.

Korea Fair Trade Commission, “About the KFTC: Organization and Mission,” (Seoul: KFTC, 2004) [online] available at http://ftc.go.kr/eng/; accessed 10 June 2004.

“Fair Trade Boss Pushes Relaxed Movie Quota System,” JoongAng Daily (Seoul), 31 October 2003

Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Trade, “About the Ministry: History,” (Seoul: MOFAT, 2004) [online] available at http://www.mofat.go.kr/en/about/e_about_ora_history.mof; accessed 12 June, 2003.

“Officials Clash Over ‘Infant Industry’ Help for Films,” JoongAng Daily (Seoul), 13 June 2003

Joon Soh, “Screen Quota Is About More Than Money,” Korea Times (Seoul) 19 June, 2003.

Korean Film Commission, Number of Screens 1991-2002 Korea Cinema Yearbook 2003 (Seoul, Korea: Korean Film Commission, 2003), 162.

Global Film Exhibition and Distribution, “Korean Exhibition Environment,” in CJ Entertainment December 2003 Press Release (Seoul: CJ Entertainment, 2003), 6.

MCT, “About the Ministry of Culture and Tourism: History,” (Seoul: Ministry of Culture and Tourism, 2004) [online] available from http://www.mct.go.kr/english/M_about/history.html; Internet; accessed 13 June 2004

Lee Yeon-Ho, “Mapping the Korean Film Industry,” trans. Im Hyun-Ock, Cinemaya N. 37, winter 1997.

CDMI, “Newsletter – KCCD, Korean Coalition for Cultural Diversity,” (Seoul: CDMI, 2003) [online] available from http://www.screenquota.org/epage/upload/Newsletter%202003.4.doc; Internet; accessed 13 June 2004.

Park Sung-soo, “Viewpoint: Whose Interests are being served?” JoongAng Daily (Seoul), 8 June 2003; “Officials Clash,” JoongAng Daily

CDMI, “About CDMI: Who We Are,” (Seoul: CDMI, 2003) [online] available from http://www.screenquota.org/epage/about/about_01.asp; Internet; accessed 13 June 2004.

Korean Film Council, “2003 Box-office Wrap-up” (Seoul: Korean Film Commission, 2004) [online] available at http://www.koreanfilm.or.kr/news/news_view.asp?kor_news_num=24&page=3&p_part=1

&p_item=&tmp_cnt=24; accessed 10 May 2004

CDMI, “Screen Quota and the Korean Film Industry,” (Seoul, CDMI) [on-line] available from http://www.screenquota.org/epage/Board/view.asp?BoardID=4&Idx=119; Internet; accessed 1 May 2004

Korean Film Commission, “Trends of Korean Film Production and Importation 1993-2002” Korea Cinema Yearbook 2003 (Seoul, Korea: Korean Film Commission, 2003), 318.

1 Comments:

India's finest decorative arts for luxury home furniture and interiors. Our collection is custom created for you by our experts. we have a tendency to bring the world's best to our doorstep. welfurn is Bathroom Interior Designsleading Interior design company that gives exquisite styles excellence in producing and Quality standards. will give door-step delivery and can complete the installation at your home.

2:41 AM

Post a Comment

<< Home